“Tu Tambien Tienes Una Madre”

“Recuerda que tú también tienes una madre-“ (Remember that you also have a mother), the man said, just loud enough to be heard but soft enough to not further aggravate. On that dimly lit street, and for reasons that I don’t fully understand, this phrase defused the rage in the other man, who slumped his shoulders, and shuffled down the street. Moments before, I had tackled the enraged man and forcefully confiscated his kitchen knife. Although still very risky, this seemed the better option rather than let him attack his former partner and mother of their child, who had run up to me in hysterics hiding herself behind my back.

Our team had been trying to de-escalate the growing tension between this couple the whole afternoon. To add more fuel to the fire, he had been drinking – able to have a conversation but with much less of a filter. Nothing was working, and as evening became night, the tension between them was growing and finally exploded into his knife attack. Even after his knife was confiscated, he promptly found a glass bottle, broke off the end, and began threatening his partner once more. If anything, he appeared more angry than before.

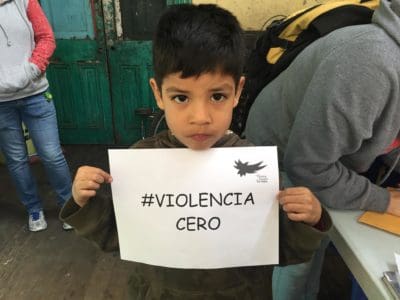

A boy holds up a sign during check in at the launch of WMF Peru’s newest ministry, “Zero Violence,” a workshop for protection and conversation advocating against violence.

Until, that is, he was gently reminded to whom he owes his life, and from where, and whom, he came. I was surprised and amazed that this actually worked, more so because it didn’t seem to be the result of any plan or strategy – it just came out, from the heart, right when it was needed most. One more glance over at this soft-spoken man revealed numerous scars and tattoos up and down his arms and neck. Seemingly, he was also familiar with the street – the fear, the cravings, the loneliness, the pain. So often those who find themselves on the street try really hard, daily, sometimes moment by moment, to forget where they are from because there is so much pain there.

And yet, to remember that we come from somewhere, that our lives are more than just random tragedy, that there might be, hopefully, someone who still cares about us, is power. A good power, the kind that helps us get up in the morning, to hold our heads up high in the face of struggle and suffering, also the kind that reminds us it’s time to calm down, to stop hurting each other and remember that we are connected.

Peruvians, I think, uniquely understand the importance of “place.” Every child growing up in Peru hears their family members, preschool teachers, newscasters, and professional athletes talk about the “Orgullo de ser Peruano.” (The Pride of being Peruvian). I, of course, didn’t “get it” for many years, even after learning Spanish and living and working and raising our children alongside Peruvians for almost two decades. Peruvian pride didn’t quite square with my American cultural values of military victory, political power, and economic wealth as deep sources of national pride. In Peru, one of the most cherished and repeated military stories is of when the horse-mounted general Ugarte rides off a cliff into the sea, flag in hand, rather than be captured by the Chileans during the Battle of Arica. During this battle, Peru permanently lost territory to Chile. The struggle to forge identity is much bigger than winning fights – those who have lost their share of fights are keenly aware of this fact.

As long as Peru has been a nation, her people have never been the strongest, wealthiest, or most powerful. But the amazing and diverse lands in which they live and create their communities are composed of coasts, mountains, and jungles – a unique topography found few places in the world. And every region has her own language, customs and flora and fauna, as well as dances, costumes, songs and food. All Peruvian children grow up hearing about this, learning the songs and the dances from their town and region, as well as going to events where they see, consume, feel and practice the songs, dances and food from other regions.

A girl crafting during Zero Violence.

Our three children have spent their whole lives steeped in these wonderful and powerful Peruvian traditions. They deeply feel the pride of being Peruvian. Truth is like a fish who is now out of water, and I am slowly realizing how deeply I also feel this pride now that we have moved to the United States. Part nostalgia to be sure, but also the fruit of thousands of shared meals, of smelling the cool crisp mountain air blowing against your cheeks while sipping coca tea among friends and of watching our children stiffly dressed in brightly colored costumes perform their dances before their parents’ and teachers’ rapt attention. It is also the countless times when, feeling very much like a foreigner, Peruvian friends and co-workers softly said to me, “You are one of us now, and we’re so glad you are here.”

To remember that we also have a mother is a powerful reminder that our lives are connected to others and to shared experiences. For most Peruvians, this is a path that reminds them of the difficult circumstances of their childhoods – households often lacking, rarely winning against opponents of all kinds, and being taken advantage of by those more powerful. A path of shared humility for sure. And yet, it is these very circumstances that, surprisingly, become fertile ground for a robust sense of identity and belonging.

The Advent season involves movement on this same path – remembering that we all “come from somewhere”, that no matter how humble, painful, sinful or tragic our beginnings, God was always there. The places from which we come become the fertile ground of our new identity for those who receive what God is doing through the salvation story. It is the pride of realizing that God not only joins us in our story but has done everything needed to include and embrace us into the great divine story of abundant and eternal life.

ABOUT BRIAN & RACHEL LANGLEY

ABOUT BRIAN & RACHEL LANGLEY

Brian and Rachel Langley, moved to Peru in October, 2000 to work with the Word Made Flesh community serving among young people who were living on the street. They served 17 years based out of Lima. In June 2017, their family moved to Columbus, Ohio. Both Brian and Rachel continue to serve on the board of WMF Peru.

CONNECT WITH BRIAN:

brian.langley@wordmadeflesh.org